Calypso

This page contains some information about the 1950s Trinidadian card game Calypso.

Although there are a few other places online with some information about the game, it doesn't currently have a huge presence on the web. This page aims add a few useful bits and pieces, and fill a couple of gaps.

Skip ahead to read the rules, follow an example game, read a little bit of strategy, see information on variants and related games, find places to play Calypso, read a little about the history of the game, check out some probabilities and numbers around the game, see other resources for the Calypso enthusiast, or get in touch.

It has been variously described (contemporaneously) in tag-line terms as:

- "The four-trump game" (This is an accurate description, if a little terse. But then again no-one wants a verbose tag-line.)

- "the new british card game" (Well, sort-of. The game originated in Trinidad, and was further developed in Britain. Of course, at that time Trinidad had not yet obtained independence from the British Empire, but claiming the game as British, although very much in-character, feels a tad unfair to me.)

- "The new card game with Bridge & Canasta features." (I suppose so, if you take a fairly broad view of the term 'features'. I mean, both Calypso and Bridge are partnership trick-taking games with trumps. But so is Whist, and given that the things that make Bridge distinct from Whist (an auction, dummy) are absent in Calypso, it might have been a more accurate comparison. As for Canasta, the similarities are 'you collect sets of cards', though in Canasta these are of the same rank, and in Calypso the same suit. So probably a better comparison would be Rummy, where same-suited runs feature in the game. So I think "The new card game with Whist & Rummy features." is a truer representation. I suspect Bridge and Canasta were chosen instead as they were both popular at the time, so trying to piggyback a bit on their success.)

There is without doubt a heavy luck element to any individual game, which may not appeal to all (although see variants and related games for some attempts to address this), but there is certainly enough freedom for skillful play to become relevant, especially over the course of a number of games.

Game Overview

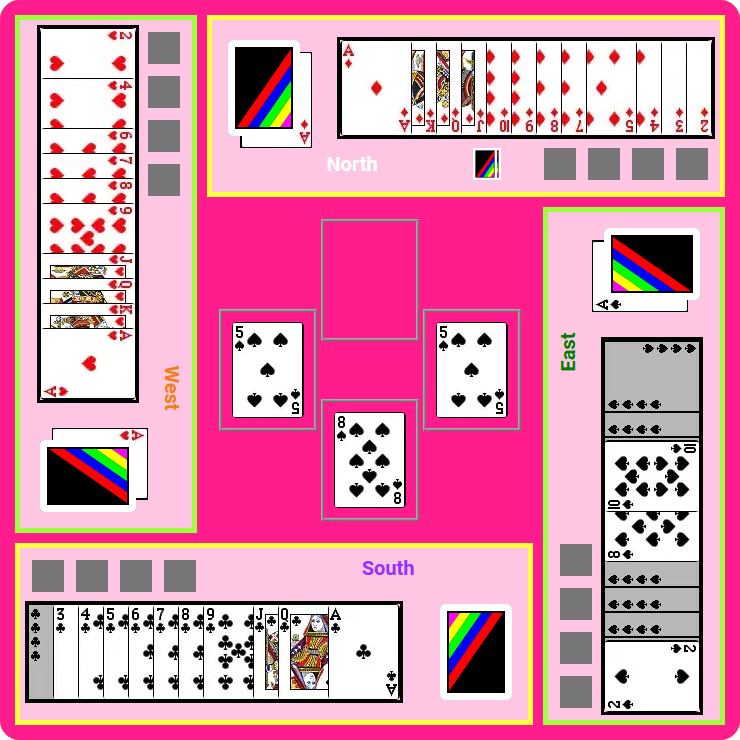

Calypso is a card game for four players, played with four identical standard 52-card packs of cards. It is a trick-taking game, played in partnerships, where each player has their own distinct trump suit, with the primary aim being to collect cards of this suit in 13-card runs called 'Calypsoes'.

A game takes place over four deals, with a quarter of the deck being dealt out for each, so that after the fourth deal you have made it through the entire deck. The rules are fairly straightforward, and can be picked up in five or ten minutes, although a couple of the rules of trick-play can take a moment to get used to. A single game tends to lasts around twenty/twenty-five minutes.

The feel of the game is much less like a plain-trick card game (where the number of tricks you win is what matters), and more like a point-trick card game (where the cards you win in tricks matters), although an unusual one given that the value of cards changes during play.

Rules of Calypso

There are a few places online with the rules of Calypso available, but I doubt one more could hurt, particularly as there is one particular rule that is often explained ambiguously, or sometimes outrightly incorrectly (as far as the original rules go). I'll try to be as explicit as possible (meaning clarity, rather than rudeness), but hopefully without getting too bogged down in technicalities.

Setup

To play the game you will need four players. There are versions for three, five, six, or more, but I'm not going to talk about those here - you can find details in the variants section, although they all require an understanding of the standard partnership version, so you should probably keep reading unless you are already well-versed.

If you have managed to gather together four of you and are feeling pretty smug and ready to start playing - hold on a second! You are also going to need some playing cards. You will need four 'standard' 52-card decks of cards (sometimes called 'Bridge decks' or 'Poker decks'), ideally with a matching back-pattern (though you can get away with mismatched packs if needs be). These together form a 'quad-deck' of 208 (= 52 x 4) cards, with each rank (from low to high: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, Jack, Queen, King, Ace) and suit (unranked: Clubs, Spades, Hearts, Diamonds) combination appearing four times. You will also need a little bit of a flat surface, such as a table, to play on (as there will often be a few cards laid out during a game - not so easy for example playing on a bus), and something to make note of the scores at the end of the game (pen and paper, a phone, computer, chalkboard - whatever tickles your fancy). You might also want to find something to serve as renounce indicators.

The game is played in partnerships (i.e. two teams of two, playing against each other), with each player having their own personal trump suit, with Spades and Hearts playing against Clubs and Diamonds (if you are a Bridge player you can think of this as the major suits versus the minor suits, although in Calypso there is no hierarchy; each suit is as good as any other). If you have already agreed partnerships, suits, and who will deal first, then you can skip ahead to the deal, otherwise this is the 'official' procedure for deciding (official according to the book of Kenneth Konstam. And I suppose me, by virtue of this page. But do whatever you want, no-one is going to come after you if you do something different, or proclaim your game of Calypso as 'invalid'.):

- Each player cuts the deck. Cards are ranked from Ace (high) down to 2 (low), and for this purpose suits rank as in Bridge: Spades (high), Hearts, Diamonds, Clubs (low). Any players cutting identical cards should cut again to break the tie, repeating until they have distinct cards. Their ranking with respect to the other players depends on their first card cut, however - these subsequent cards are only to break the ties between players with identical cards.

- The player cutting the highest card has choice of personal trump suit, and will be dealer for the first hand. The player cutting second-highest will be their partner, and therefore have the complementing personal trump, and sit opposite. Third highest has choice of the remaining two seats (i.e. on the left or right of the dealer) and personal trumps, with the fourth player taking the remaining seat and trump suit.

The deal

The deck should be shuffled thoroughly before the game begins, particularly if you have just played a game of Calypso, as suits will naturally end up 'clumped together'. In practice, to shuffle it might prove easiest to divide it up into batches to be shuffled separately, before recombining and shuffling all together (and perhaps repeating this process a few times), as a 208-card deck is pretty cumbersome to handle directly. The deck will not need to be shuffled again for the duration of the game, so feel free to take a little longer shuffling than you ordinarily might for a game where you shuffle between each hand. Once the deck is properly shuffled, the first deal begins.

For each deal, the player to the right of dealer cuts the remaining deck, and the dealer then deals thirteen cards to each player, one at a time, beginning with the player to their left, and continuing sunwise (i.e. clockwise). Similarly to shuffling, it may prove useful for dealing purposes to try and lift a smaller portion of the pack to deal with, and taking an extra batch from the top of the deck if you run out of cards in your batch before everyone has thirteen. Once the cards have been dealt, the remainder of the deck is passed to the player left of the dealer, who places it at their left. This will not be necessary on the fourth and final deal of the game, as at that point the deck should be entirely exhausted (although see irregularities for how to handle the situation where you end up with extra cards leftover, or not having enough).

After the hand is finished, the player to dealer's left (who will have the deck-remainder at their left) will be the dealer for the next hand, following the same procedure as above, except without the need to reshuffle. This continues until all four players have dealt exactly once - in this way the entire deck ends up dealt out over the course of four hands, a quarter at a time.

Trick-play

The rules of trick-play can take a bit of getting used to, but ultimately are not too complicated. However, the rules as written in several sources (including 'official' sources such as Konstam's book) are sometimes worded ambiguously, so I shall try to make these crystal-clear, and furnish enough examples for reference.

In terms of admin, left of dealer leads to the first trick of a hand, and thereafter the winner of each trick leads to the next, until the hand is finished. Players must follow suit if able, but if unable may play any card. These are the same rules as in many other games, such as (to name only a few) Bridge, Whist, Spades, Skat, Piquet, Solo, and Oh Hell! (and is expressed as f,tr in Parlett's notation).

Players who are not leading to a trick will therefore do one of three distinct things:

- Follow suit to the card led

- Trump in - meaning to play their personal trump suit when not following suit

- Discard (also known as renounce, or renege), meaning to play a suit different to the suit led or their personal trump suit

Note that players must follow suit if able, otherwise they may freely choose to either trump in or discard. If a player is following suit to a trick in their personal trump suit, then following suit is not deemed to be trumping in - by definition you can only trump in when you are not following suit. Thus, if your personal trump suit is led, in that trick your options will only ever be to follow suit (which you must do if able) or discard (which you will be forced to do if you cannot follow suit).

The rules governing who wins the trick are as follows:

- If any player trumps in, then the player trumping in with the highest card wins the trick (with ties going to the first played). This means that any trick where someone trumps in can never be won by the player who leads to the trick.

- If no players trump in, and the card led is not the personal trump suit of the leader, the trick is won by the highest card of the led suit (with ties going to the first played).

-

If no players trump in, and the card led is the personal trump suit of the leader, then they

win the trick regardless of any ranks played.

- Another way to put this which I think is quite helpful, as described by Charles Goren, is that if a player leads their personal trump suit, it is as though they have led an Ace, regardless of the actual rank played (but the suit has no special privelege beyond that - if anyone else plays a trump, the leader is trumped, and cannot win the trick).

The problem rule

There is one rule in particular which is often not clearly written, is a frequent point of confusion for newcomers, and is sometimes outright stated incorrectly. This is what occurs when a player trumps in to a trump lead, and they play a card which is lower in rank than the leaders card. The rules outlined above already cover this case, and hopefully make enough sense that no further clarification is necessary, but I want to be agonisingly clear on this point: In such a case the winner of the trick can never be the leader, and will always be a player trumping in, regardless of the rank of the led card. Two things follow from this fact:

-

If you lead your personal trump suit, the rank of the card is

completely irrelevant to winning the

trick (although the rank matters for forming Calypsoes).

If no-one else trumps in, you win the trick, or if someone else does trump in, you will lose the trick.

As far as winning the trick goes, leading a 2 is just as good as leading an Ace.

- In an equivalent way to think about it, as described by Charles Goren, leading your personal trump suit is just the same as leading any other suit, except that the card led acts as though it were an Ace.

- No lead is safe - no card led will guarantee you winning the trick (until a stage in the game where you know enough about your opponents' hands, or remaining cards that you needn't worry). Whatever suit you lead, if someone else trumps in, you will not win the trick, regardless of the rank of your lead card. This is in contrast to most trick-taking games, where leading the Ace of trumps ( or whatever the highest trump is in that game) will usually guarantee winning the trick.

This confusion in this rule often arises from use of phrases along the line of 'the highest personal trump played wins the trick', but what is not clear from this phrasing is that this does NOT include any personal trump which led the trick. Even some of the 'official' rules phrasings are ambiguous around this point, although fortunately various examples of play clarify precisely exactly how this works. As such, on this page you can see some example tricks below to help clarify this (as well as the other rules of trick-play).

Aside from the above point of confusion, the two other things that can trip up new players are the facts that:

- You win tricks when leading your personal trump suit if everyone follows suit, regardless of the ranks played,

- following suit to a trick of your personal trump confers you no special benefit - the only way you can win the trick is by playing the highest card. In other words, if you are following suit, you are never considered to be playing a trump.

Example tricks

As these rules can take a bit of digestion, it is perhaps useful to outline a bunch of example tricks to show the rules in action. In all cases the leader is North, the Spades (♠) player.

| North (♠) | East (♦) | South (♥) | West (♣) | Winner | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 ♠ | 6 ♠ | K ♠ | 4 ♠ | North | Led personal trump, no-one trumped in |

| A ♠ | A ♠ | 3 ♠ | 4 ♠ | North | Led personal trump, no-one trumped in |

| 10 ♠ | 6 ♣ | J ♠ | 2 ♠ | North | Led personal trump, no-one trumped in |

| 10 ♠ | 6 ♦ | J ♠ | 2 ♠ | East | Trumped in, no-one else did (NB the problem rule - East wins despite 6 being lower than led 10) |

| 10 ♠ | 6 ♦ | 6 ♥ | 2 ♠ | East | Trumped in, no-one else played a higher trump (South only tied - ties go the earliest card). (NB the problem rule - East wins despite 6 being lower than the led 10) |

| 10 ♠ | 6 ♦ | 7 ♥ | 2 ♣ | South | Trumped in with the highest trump played ('overtrumping') (NB the problem rule - South wins despite 7 (and 6) being lower than the led 10) |

| 10 ♠ | 6 ♦ | 7 ♥ | 9 ♣ | West | Trumped in with the highest trump played ('overtrumping') (NB the problem rule - West wins despite 9 (and 6 and 7) being lower than the led 10) |

| 3 ♦ | 6 ♦ | K ♦ | 4 ♦ | South | Highest card of (non-trump) suit led. Note that East is deemed to be following suit here, and holds no special position just because their trump suit is Diamonds. To win the trick they would have needed to play the highest card. |

| 3 ♦ | 6 ♦ | K ♦ | K ♦ | South | Highest card of (non-trump) suit led (ties go to earliest card) |

| 3 ♦ | A ♦ | K ♦ | A ♦ | East | Highest card of (non-trump) suit led (unrelated to the fact that ♦ is East's trump suit) |

| 3 ♦ | A ♣ | K ♦ | A ♦ | West | Highest card of (non-trump) suit led |

| 8 ♦ | A ♦ | 4 ♥ | A ♠ | South | Trumped in (no-one else did) |

| 8 ♦ | A ♦ | 4 ♥ | 2 ♣ | South | Trumped in (highest card to do so) |

| 8 ♠ | 8 ♠ | 8 ♠ | 8 ♠ | North | Led personal trump, no-one trumped in |

| 8 ♦ | 8 ♦ | 8 ♦ | 8 ♦ | North | Highest card of (non-trump) suit led (ties go to earliest card) |

| 8 ♠ | 8 ♦ | 8 ♥ | 8 ♣ | East | Trumped in, no-one else played a higher trump (the other two only tied - ties go the earliest card) |

Renounce indicators

In card games, people make mistakes. Through unfamiliarity with the game, distractions, or brainfarts, sometimes players will play a card that is not legal for them to play, which must be dealt with in some way. However, in practical terms, Calypso offers a couple of challenges for being able to keep track of this.

One aspect that makes it slightly challenging is the fact that, from the 208-card deck, only a quarter of the cards are in play in any individual deal. This means that the exact cards in play during a deal are generally not known until the end of it, and so it can be harder to keep track of the different suits, and knowledge about players' holdings in them. For instance, in Bridge, say, if 8 spades been played, and you hold five in your hand, you already know that no other player can have any spades left. Usually you are not in a position to be able to make such a deduction in Calypso.

A more challenging (from a practical point-of-view) consideration, however, is the fact that tricks are 'destructive'. At the end of a trick, some cards may go into a trickpile, while others may go to the in-progress calypsoes of the trick-winner, or their partner. This 'forgetting' of where cards have come from means that it is not possible, in general, to inspect previously-played tricks. Thus in cases where there is some dispute or query about previous actions in a deal ("You just followed suit to that hearts trick, but I'm sure earlier on you played a trump to one") there is no way of checking, as there tends to be in most other trick-taking games (where cards are often collected as individual trick-packets, or players retain their own cards in trick-order so that trickplay is recreatable).

For these reasons renounce indicators were introduced as part of the boxed sets, as well as being baked into the laws of the game. The Calypso book by Alfred Sheinwold contained a page of these indicators so players could cut out a full set, should they be lacking. Each player has four of these — one for each of the four suits. They must be something that can exist in two states — 'off' and 'on'. These usually take the form of cards that on their face say, for example, 'The Clubs player has not followed suit to Hearts'.

All players start a deal with these face-down ('off'), and then when a player fails to follow suit for the first time to a suit, they must turn the appropriate indicator face-up ('on'). This means that all players can see which suits each other player have failed to follow suit to in a given deal. If a player neglects to turn their indicator up, they can be prompted by the other players. At the end of deal, these are all turned face-down once more.

If you do not have a set, you can improvise with pen and paper, or with a separate (fifth!) deck of cards if you have one (ideally quite different looking, so as not confuse them with in-play cards. I find a miniature deck works quite well, with each player using all four cards of a different rank).

Should a player commit a revoke in a competitive game, the opposing side receives a bonus of 260 points. The cost is especially steep as the difference of a few cards can mean the difference between an incomplete and a complete calypso - this being the minimal price difference between them.

Collecting calypsoes

The primary aim of the game is for players to collect Calypsoes - these are thirteen-card collections in their personal trump suit, with precisely one card of each rank, from 2 up to Ace. As a Calypso is being built up, the cards towards it are placed face up on the table in front the player. During a game there will usually be partial Calypsoes in front of each player. These must be placed so that everyone in the game can see all of the cards that each player has towards their Calypso. Players can only build one Calypso at a time - they must complete their first before accumulating cards for a second.

As well as an area for placing in-progress Calypsoes, players will each need a pile to put completed Calypsoes (which they stack face-up), and a face-down trick-pile where other cards will go. Players only need one trick-pile between each partnership.

When a player wins a trick, they gather together the four cards played to the trick, and distribute them accordingly:

- Any cards of their trump suit they do not already have as part of their Calypso-in-progress will be laid in front of them, face up (arranged in ascending order, usually with cards partially overlapping, but such that all cards are visible)

- Any cards of their partner's trump suit not already part of their Calypso-in-progress will be passed to them to likewise lay face up.

- Any card of opponents' trump suits, or duplicate cards from Calypsoes, go face down to a pile in front of the player in their trick-pile (although note the exception below).

When a player completes a Calypso, the thirteen cards are gathered up into a pile, and laid face-up next to that player's trick-pile. They are then entitled to start building up cards towards a new Calypso. There is an exception, however, to duplicate cards being discarded to the trick-pile: if a player completes a Calypso with a card from a trick, any would-be duplicates in that trick can instead count towards the new Calypso. Say, for example, a player needs only the 7 for a Calypso, and wins a trick with 7, 8, 8, K of their trump suit, they will take the 7 (thus completing the Calypso), lay down 8, K towards the new Calypso, and add the duplicate 8 to their trick-pile. This happens regardless of the order of the cards played to the trick.

Scoring

Play consists of four deals, so that after the fourth hand all 208 cards have been played to tricks, over the course of those four deals. Only at the end of the fourth hand is the game scored. Players then receive the following points:

- Points for each completed Calypso

- 500 points for their first

- 750 points for their second

- 1000 points each for a third or fourth

- 20 points for each card towards an incomplete Calypso

- 10 points for each card in their trick-pile

Note that partners score for Calypsoes separately - partners with a single Calypso each will score 500 + 500 = 1000 for these, rather than 500 + 750 = 1250. After this calculation, partners add their total scores together, and the partnership with the highest score wins.

Calypso strategy

Having read the rules to Calypso you know how to play the game, but you may not yet know how to play. While there is undoubtedly a reasonable luck factor to an individual game, there is certainly room enough to flex some tactical muscles in the game. All the books on Calypso dedicate a considerable number of pages to discussing strategic considerations.

If you are a complete novice and/or just wish to avoid irritating a more experienced partner, a quick simple guide that will serve you pretty well is:

- Try not to lead your partner's trump suit

- Lead high cards (A, K) of your opponents' suits

- Lead low cards of your personal trump (but try to keep some saved!)

- If your opponents are likely to win a trick, throw cards that duplicate cards they have in their calypsoes, whilst if partner is likely to win, try to contribute non-duplicate cards

There is more detail on these points (and others) in what follows (and I will gradually expand this section), but following those points shouldn't steer you too far wrong. At the very least it should certainly help you navigate your first few games without any major blunders.

General advice

Calypso is a game about collecting cards of your trump suit, and your partner's trump suit. First and foremost in your mind should be to trying to make sure your partnership ends up with cards needed to complete calypsoes, whilst denying your opponents the same. In tricks that you are likely to win, focus on getting cards your partnership needs towards their next calypsoes, and discarding cards your opponents need. On tricks that you are likely to lose, discard cards (where possible) that are not useful to you or your opponents.

On the other hand, do not focus so much on collecting calypso cards that you neglect to win tricks full of 'useless' cards. I often like to think of Calypso as point-trick game, where the points each card is worth are context-dependent. From this angle:

- 'Plain' cards (those of your opponents' suits, and duplicates of your own; anything that ends up in the trickpile) are worth 10 each

- Cards that end up in incomplete Calypsoes are worth 20 each

- Cards that end up as part of a completed calypso have value dependent on which of your calypsoes they

comprise part of:

- For your first calypso they are worth 500/13 ≈ 38 points each (I usually think of this as 'a bit less than 40')

- For a second calypso they are worth 750/13 ≈ 58 points each (just under 60)

- For a third or fourth they are worth 1000/13 ≈ 77 points each (a few shades under 80).

In practice it is comparitively rare to get more than one calypso individually, so for the majority of cases a calypso card is worth at most around four times a 'plain suit' card. While this is certainly significant, it is not earth-shattering - a lot of tricks in the game will end up in the trickpile, and winning four of these is (almost) just as good as winning a trick with all cards going towards calypsoes. As Alfred Sheinwold says in his section Don't Sniff At The Junk Pile: "If you pay careful attention to winning as many tricks as possible, you will tend to get your fair share of calypso cards and you will tend to keep away from the opponents some of the calypso cards that they need. At the end of the game you will be far better off than the player who keeps his eye peeled for calypso cards but doesn't care much about the other tricks."

I know from experience that it is possible to win a game despite having fewer calypsoes than the opponents, which ultimately comes down to making up the difference with extra cards in the trickpile.

Leading

A lot of the focus of Calypso strategy is around what to lead. Despite the fact (at the start of a hand at least) no leads are safe, choice of lead can have a big effect on the likelihood of your partnership winning the trick (or of winning future tricks). The most important aspect is in regards to the suit you will lead.

Leading your own trump suit

Leading your own trump suit is pretty tempting. If everyone else follows suit, we automatically win the trick, regardless of the ranks of the suit we or anyone else has. It also starts us accruing cards towards our next calypso.

There are a couple of downsides though. One is that opponents will be aiming to discard cards that duplicate ranks already present in your calypso-in-progress, or within the trick itself, which can limit your ability to complete multiple calypsoes. If opponents run out of your suit, you may also lose key cards if an opponent ruffs. It may also limit your own ability to trump in later in the hand, and thus regain the crucial lead.

As such, leading your own suit is usually best when you have only a few low-ranked trumps. There is little point saving them for ruffing, as they are more vulnerable to being overpowered by other trumps, but more seriously they are likely to be lost when an opponent leads a high card of your trump suit.

If you have a high card, such as an ace, or perhaps a king, it may be best to play on another suit, as you are likely to be able to win back the lead if your trump suit is led by an opponent. It may also prove useful in trumping in to a crucial trick.

Leading opponents' trump suit

The fact that in Calypso everyone has a unique trump suit means that when you lead a suit, you are only 'drawing trumps' for one specific player. Leading the trump suit of one of your opponents means that they lose a trump (if they still have any), while you don't. Thus it is often very advantageous to do so. It also means that the opponent in question is unable to trump the trick - the only way they can win is by using high cards of their suit.

If you have a high card of an opponent's suit, this is nearly always a useful lead. An ace in particular (or king if the aces have all been out) gives a very high chance of winning the trick - the only way to lose it is if opponent's partner trumps in. This allows partner the opportunity to safely discard any cards they have that are needed for opponent's calypsoes, as well as depleting the relevant opponent of valuable trumps. With a few high cards of their suit, you may be able to bleed them of all their trump holdings before they get a chance to benefit from them. An opponent who you know holds no trump cards is very advantageous, and allows you to play cards more safely.

Of course, there are two opponents, so a natural question to consider is which of their suits to lead? Obviously if you hold high cards in one that is useful as it makes it more likely to retain the lead, but beyond that there are a couple of things to consider.

If you hold more cards in one than the other, it is usually best to lead the longer. This gives you more opportunity to 'outlast' the player whose suit it is, and thus have some length winners. If there is nothing between them, then it tends to be better to focus on the suit of your right-hand-opponent. If you deplete them of trumps, then any remaining winners you have in the suit allow partner to play whatever they like to safe in the knowledge that fourth hand will not be able to win the trick.

Additionally of crucial consideration is the situation with calypsoes. If you hold cards crucial for an opponent to complete a calypso you probably don't want to leave that card exposed by playing off others in the suit. If they need one or two only, say, you may be inclined to play aces of this suit so that partner can (relatively) safely get rid of these missing ranks if they hold any.

Leading your partner's trump suit

You should be wary about leading your partner's trump suit. Any such lead means that partner is unable to trump in, whilst both opponents potentially can. It also depletes partner of a trump card, which they may well need later in the hand. Another potential danger is the fact that, if partner turns out to be out of cards in their suit, you risk exposing this information to the opponents unduly.

There may be occasions when it is necessary. For example, if partner needs only an Ace for a calypso, and you hold one, cashing this in a fairly safe manner may be a good idea (although consider whether you may be able to win back the lead with this from an opponent's lead of the suit). A singleton Ace, also, may be in danger of being lost if an opponent leads another Ace of this suit, so may be prudent to cash. It may also be that this is the 'least bad' option, compared to other suits you hold - or you may simply have no other suits from which to lead.

Nevertheless, if you are about to lead your partner's trump suit, you should always first ask yourself if it is really a good idea to do so. Partner will rarely thank you for doing so if you had other, more sensible options available instead.

Conventions

In plain-trick card games, if you are not going to win the trick, then it doesn't really matter what card you play (beyond retaining cards that will be of use in the future/discarding problematic cards). This means that the choice of card to play can instead be used to convey some information - for instance Contract Bridge makes frequent use of card signals of various sorts.

In point-trick games there is a bit less scope for this, as the choice of cards to add to tricks often has direct game implications (although some games do employ such systems, such as Cointrée), and Calypso in particular often presents situtations where the choice of discard is goverened by denying/supplying required cards.

Nevertheless there is potential scope for (limited) card-signaling conventions. Jo Culberston recommends a couple of conventions you may wish to experiment with, which I outline below.

For what it's worth, Alfred Sheinwold discourages bothering with conventions, saying "Calypso is not really a complicated game, but there is quite enough to think about during the play. There is no need to drag in unworkable signals that can succeed only in distracting your attention from the plays that you really should be noticing.". Ewart Kempson (admittedly writing slightly earlier) agrees: "...I have no doubt that great efforts will be made to introduce artificialities, but, as yet, I am unable to see how they can succeed. To arrange a series of card signals, such as playing a high card before playing a low card, or discarding from one suit instead of another, will do a partnership far more harm than good—or so, at least, it seems to me.".

So perhaps see what you make of these, and experiment with them to see if they are worth the trouble.

Doubleton echo

The basic principle of this convention should be familiar to Bridge players. It gives a means of conveying to partner the information that you have precisely two cards of their trump suit. To enact it, if partner leads two rounds of their personal trumps, you play your higher card of that suit to the first trick, and the lower card to the second trick. On the second trick, partner will see that you have played lower the second time round, and will take that to mean that you:

- have no further cards in their trump suit,

- wish them to continue leading it.

The idea is that if you only hold two cards of partner's suit, the opponents likely have more, so partner can safely play a third round, giving you the opportunity to discard problematic cards (such as one needed to complete an opposing calypso), or perhaps even to take the lead by ruffing partner.

Of course, game circumstance will dictate whether, when holding a doubleton in partner's suit, you wish to actually signal the echo - if not, you must then play the cards in ascending order so as to not mislead partner. I am personally not sure whether the advantages of using the echo outweigh the cost of constraining your play to partner's suit (as note for example that any time you have more than two cards of their suit, you must play the first two in nondescending order). I think it at least is worth experimenting with - probably the constraint is not too costly in most circumstances anyhow.

Suit signals

Culbertson also outlines some basic conventions for discarding on partner's lead (when you hold no cards of their suit) to signal which opponent's suit to attack. The convention is that to discourage partner from leading a particular suit, you first discard a card of that suit, followed next by a card of the opposite suit. For instance, say partner leads their trump suit (Hearts), and you have no Hearts, but have both Clubs (headed by an Ace), and Diamonds (headed by a ten). You are much more likely to win the lead if partner attacks Clubs before Diamonds. As such, on partner's Hearts lead, you first discard a Diamond (indirect/discouraging signal), and if partner leads another Heart, you clarify this by discarding a Club.

The idea is that primarily your discard strategy will be to attempt to void yourself in a short suit, so that partner may give you ruffs. Generally, then, partner will assume that the suit you discard initially is one you are short in, and will in due course lead this suit to allow you to trump in. This convention then allows you to tell partner you have no prospect of ruffing, by discarding from both suits. The logic in having the first suit be the one you don't want led is that:

- If you only get to discard once, then this is the safer assumption for partner to make (if you do want this led because you aim to ruff, this will not change as the hand goes on, so there is no cost if partner is misled in this way)

- Also if you discard only once, you retain cards in your stronger suit

There is another layer to this, however. There may be situations where you wish to strategically discard, but still encourage the lead of the suit. For example if you hold Axx, and want to leave yourself with just the Ace - discarding two of these followed by the opposite suit may be read as discouraging. You may also have 'danger cards' you want to unburden yourself of (say those that would complete an opponent's calypso), but also hold a stopper.

Culbertson allows for this situation with the following convention: two discards of the same suit in an echo (discarding the high card first, then the lower card) is to be read as encouraging. This addition provides a further complication for the case where the discards are interrupted - a partner seeing only a single discard does not know if it is discouraging (the start of a two-suit discard) or encouraging (the start of an echo). In such a situation they will need to use judgement - a 'high' card is likely to be encouraging (start of an echo), while a low is more likely discouraging. Employing this convention, then, means that if you are intending to use two-suit discouraging, it is best to discard initially with a low card.

Although I see the benefit of helping direct partner's lead, again I am unsure if the situations where you gain useful information outnumber the situations where you are forced by the convention to discard suboptimally or mislead partner. My current feeling is that this is probably more useful than not, but am happy to hear any further insights from anyone!

Further conventions

I am not aware of any other conventions, nor have I contrived any. I would be keen to hear of any others, either from some source, or self-created. Do get in touch!

Calypso in numbers

See Calypso in numbers for probabilities relevant for Calypso, as well as various other quantitative considerations relevant to the game.

Variants and related games

There are several different variants of Calypso in existence. Many, although not all are designed to mitigate the relatively high luck factor inherent in a single standard game of Calypso, or to cater to different numbers of players in some fashion or other. If you know of any others, or have devised one yourself that you feel may warrant inclusion on this page, please do get in touch.

Variant trickplay rules

Not necessarily quite distinct games in and of themselves, but there are a couple of different sets of trickplay rules available to play.

These can of course, if desired, be combined with any of the other variant games described hereafter.

Beat the leader

Some play that the problem rule does not apply. In other words, in order to win a trick in which a player has led their personal trump suit, you must play a personal trump of a higher rank than the led card.

In my opinion this makes the game less interesting, as it makes the lead especially powerful, and means that high trumps are never really 'at risk', although your mileage may vary.

I don't know to what extent this rule developed/is played deliberately vs. a misunderstanding of the original rules.

All Fours Calypso

This is a variation of trickplay rules of my own suggestion. It combines the 'beat the leader' rule with the ability to trump a trick even when you can follow suit. In other words, the changes are:

- if a player has a card of the suit led, they must either play a card of that suit to the trick or a card of their own personal trump suit

- if a player leads their personal trump suit, the trick may only be lost if another player plays a card of their personal trump suit of a higher rank.

You can read more about the rationale behind this rule in this blog post.

This rule of course also affects the use of renounce indicators — these only need to be faced when a player discards to a trick, not when trumping ( as they are legally allowed to play a trump while still holding cards of the led suit).

The rule for following suits (ft,tr in Parlett notation) is the same as in the card game All Fours, and other related games. The fact that All Fours is a popular game in Trinidad provides a nice additional link to Calypso, and so feels like a good choice for naming this variant (even though I originally thought of it in the context of Swiss Jass games).

Originally I called this 'the Swiss rule', as I had not made the connexion to All Fours. That was even a poor fit as a name, as it should really have been the swiss-like or swiss-ish, as these rules were originally inspired by, but not quite the same as, those played in Swiss Jass games. If those games are more familiar to you, then you may refer to this as Swiss Calypso, or if you are in the mood for something extremely tortuous, then perhaps even Calswisspso might tickle your fancy.

Duplicate Calypso

Calypso that's so good you play it twice. Not to be confused with the Duple Calypso, a 1980s British coach design.

Kenneth Konstam, in his book, describes rules for Duplicate Calypso, much in the same vein as Duplicate Bridge (in fact he makes the incredibly far-reaching claim "Apart from Contract Bridge no other game lends itself to this test of skill which obviates the necessity for a monetary stake and turns the game into a match with the element of luck minimised.". I would say this is probably not true.). If you do ever manage to gather together eight willing Calypso players who don't mind a bit of extra admin (or possibly even more??), perhaps it is worth a try.

The version described by Konstam is for two teams of four - he calls them 'A' and 'B', but we will use a slight whisker more imagination and refer to them as the 'Adders' and the 'Badgers'. Each team is split into two partnerships - one for the 'major suits' (to borrow Bridge terminology), Hearts (♥) and Spades (♠), and the other for the 'minor suits', Clubs (♣) and Diamonds (♦).

Ideally you will need two quadruple-decks of cards (so eight(!) standard packs), so as to facilitate two games. These will be shuffled separately, each ready for a game of Calypso. The arrangement of one deck will be referred to as game 1, with the other being for game 2 (each with a fixed choice of opening dealer).

Two games occur (potentially, though not necessarily) simultaneously - the major suits Adders will play game one against the minor suit Badgers (at 'table 1'), whilst the minor suit Adders play game two against the major suit Badgers (at 'table 2'). Once both games are complete and scored, the games switch, meaning that the decks must be re-arranged into the position they were in at the start of the game. Then each foursome plays with the other deck, so that the major suits Adders will now play game two against the minor suit Badgers, whilst the minor suit Adders will now play game one against the major suit Badgers.

Obviously you will need some method of recreating the decks into their original state (or something equivalent), which is a more arduous task than in Bridge, due to the fact that

- a game consists of four inter-related deals, rather than each deal being effectively independent, as in Bridge

- it is not as simple as tricks being 'won' or 'lost', with cards going into Calypsoes, trick-piles, etc., so recreating where cards originated from (or any details of the play for that matter) is not possible (except for someone making a note of things, or via anyone with a particularly good memory)

One option would be to have an independent 'referee'/'director' to take care of this side of things, but this is probably a bit of a luxury. Another choice would be to get everyone to make a note of their cards at the start of each hand, so that they can then, at the end of the game, recreate their set of hands - perhaps placing them in envelopes labelled 'Spades player hand 1', 'Diamonds player hand 3' etc., ready to be passed to the other foursome.

Scoring for the match is then calculated by adding up the four scores for each team - i.e. summing up

- Minor suit Badgers score in game 1 (from table 1)

- Major suit Badgers score in game 1 (from table 2)

- Minor suit Badgers score in game 2 (from table 1)

- Major suit Badgers score in game 2 (from table 2)

and similarly for the Adders team. That way the luck of the cards is 'balanced' by the fact that the different partnerships of each team will play with each set of cards in the deal, and thus any differences in score between the teams arises solely through how the two teams played the same hands differently, which in theory should tend to be more skill-driven than playing individual games (where sometimes just getting great or terrible cards overrides any amount of skill involved on the part of the players).

This could of course be extended to multiple tables, to accomodate greater numbers, using a system of matchpoints, as in Bridge, where each for each game a partnership is scored in accordance with the proportion of other partnerships playing the same set of hands whom they score more than. In the unlikely event anyone should care to play the game in such a fashion I'm sure details would be fairly straightforward to hash out.

Cutthroat Calypso

There is a version of Calypso described generally in books on Calypso, where each player plays for themselves (i.e. no partnerships). It is variously called "All-against-all Calypso" (by Konstam), "Single Calypso" (also Konstam), "Four-handed Calypso" (by Kempson), or "Four-hand Cutthroat Calypso" (by Culbertson).

The rules are identical to the standard partnership version, except that upon winning a trick a player takes cards of their own trump suit only towards a Calypso, with all three other suits going immediately to their trick-pile, as players have no partners. Of course, at the end of the game, each player simply counts only their own score, with the highest being the winner.

By most accounts this is not as interesting a game as the standard partnership version, although a noteable exception is Ewart Kempson, who actually prefers the cutthroat game to the partnership one: "Generally sparking partnership games are superior to games composed of individual players, but my own preference at Calypso is towards the four-handed game where each of the players battles away against the other three. It is---when played in the right company---a really hilarious game and one in which a good player may, at times, shine. The luck in the individual game is, perhaps, even greater than in the partnership game, but there are far more openings for brilliant play. Four-handed Calypso bears some slight resemblance to one of the best of all card games---Hearts. At both, the advanced player tries to preserve a balance of power. While all out for himself, he will---when forced to give something away---strive to benefit the opponent who is furthest behind."

Three-handed Cutthroat Calypso

As well as outlining the rules of Cutthroat Calypso for four, books on Calypso also tend to describe a three-handed version. This is version is played using 'only' three packs of cards, by removing one suit from all three decks (generally unspecified which, although Culbertson gives Clubs as an example, and Parlett says that Spades is conventional. I would instead recommend Diamonds, as I think it is uncontroversial to say that this is clearly the worst of the four standard French suits), leaving a deck of 117 (13 x 3 x 3) cards of only three suits. Play is identical to the four-handed version, except that it takes place of course over only three deals.

Generally there is not much written about this version, and what is written tends to not be too positive - for instance Culbertson says of it "We do not think this variant will become popular. It scarcely admits of any strategy but leading one's personal trump to exhaustion, then resigning oneself to fate.". Even Kempson, who was a self-admitted fan of the four-handed cutthroat version has at best some pretty muted praise: "Like all three-handed versions of four-handed games, Calypso for Three is a makeshift, but it can be a vastly entertaining gamble.", and his summary I suspect will convince very few to try this version: "It is better than some other three-handed games and much better than sitting out in the rain.". While indeed there may be worse three-player card games, there are certainly a host of better ones - personal suggestions include Skat, Coiffeur, Ninety-Nine, Ulti, and Vira. Alternatively John McLeod has an even wider host of suggested options.

Both David Parlett and Alfred Sheinwold have alternate versions of Calypso for three players that attempt to address some of the shortcomings of the plain cutthroat version.

Split-partnership Calypso

David Parlett suggests a version of Calypso for three players that differs slightly from the cutthroat version. Play is identical, but at the end players get a total score which is the sum of their personal score, and that of the player to their right. This allows for some more interesting play than in the pure cutthroat form, as one is invested in helping out the right-hand player, so that the game can still capture some of the interesting facets contained in the partnership verson of the game, as it lies somewhere between an all-against-all version and the partnership version.

To simplify the scoring, an equivalent method is for your score to simply be the negative of the 'standard score' of the player to your left. This simply shifts the three scores down by a fixed amount as compared to the originally outlined method (the amount of the shift being the sum of the three standard scores).

Sheinwold's Calypso for Three

In his book, Alfred Sheinwold outlines an alternative version of Calypso for three players. He titles it simply Sheinwold's Calypso for Three but, as that is somewhat of a mouthful, I would suggest perhaps instead Neutralised Calypso.

In this version, you remove a single 2♣ from a quadruple deck, leaving a 207-card deck (a multiple of 3, note). Play is as in the usual Three-handed Calypso, except that Clubs is nobody's personal trump suit, acting instead as a 'neutral suit' - i.e. it always functions as a side-suit, which Sheinwold says "...poses interesting problems of its own.". A game consists of four deals of 13 hands each, and a fifth and final deal of 17 cards. Note that 3 x (4x13 + 17) = 207.

One could of course combine this approach with David Parlett's suggestion, to create Neutralised Split-partnership Calypso. Simply play Sheinwold's version as described here, but tally the final scores using Parlett's method of combining your score with that of your right-hand-opponent.

Calypso for Five or Six

As well as suggestion an alternate way to play Calypso with three, Alfred Sheinwold also devised rules to play Calypso with five or six players. Structurally the game is much as the standard four-player version, but with some players sitting out each hand, similarly to how things work in several other card games when you have an extra player (such as Skat, Doppelkopf, or Paskievics).

Five players play as a team of two against a team of three, whereas six players play two teams of three. In teams of three, one player sits out for each hand, with the player who has just sat out of a hand replacing the outgoing player. Players sit out alternately, such that whichever of the three sits out for the first hand of the game also sits out for the last. Care must be taken, though, as this arrangement means that individual players will have different trump suits at different points of the game. For instance, let us suppose we have a team of three, Kenneth, Josephine, and Alfred, playing the major suits. Then we would have, for the four hands:

- Kenneth (♥), Josephine (♠), [Alfred sits out]

- Kenneth (♥), Alfred (♠), [Josephine sits out] {Alfred replaces Josephine}

- Josephine (♥), Alfred (♠), [Kenneth sits out] {Josephine replaces Kenneth}

- Josephine (♥), Kenneth (♠), [Alfred sits out] {Kenneth replaces Alfred}

so that both Kenneth and Josephine play with Spades and Hearts as their personal trumps at different hands of the game.

For six, Sheinwold ensures there is no downtime for the two sitting out: "The two inactive players should be active elsewhere, or may kibitz, but they should not offer any advice or comment at any time during the play. They may help score at the end of the hand, and they may join in a discussion of the facts and the law in case of an irregularity. (Try to stop 'em!)". For five, the player sitting out has the usual options of observing, trying to grab a quick drink at the bar, nipping to the loo, or sending a message to a loved one to say that they will not be home for some number of hours as they are deep into an evening of Calypso that shows no signs of abating.

Calypso for Many

In Alfred Sheinwold's world, counting seems to go: Three, Four, Five, Six, Many (although he in fact uses the phrase 'Large Parties' - this probably, in practice, means a good twelve or more. Fewer numbers will just have to split into groups and play separate games of Calypso.).

In his unfailing mission to cater for a wide variety of group sizes, Sheinwold gives yet another option for playing Calypso (coming in two slightly different flavours - for partnerships or for individuals), in some ways similar to Duplicate Calypso (but without the duplicate part), and not dissimilar to a Whist drive or Progressive Bridge. We might refer to this as Progressive Calypso (which is incidentally the name of a Calypso song by Tinou Lavital).

You start off with a series of tables - enough for one per foursome, each given a sequential number. Each table needs its own 208-card deck. Ideally you will have a multiple of four people, but if not you can account for the extras by having some tables play with five or six. Over the course of the session, each table will be a playing a game simultaneously. Sheinwold suggests a host/director makes periodic announcements to ensure everyone is approximately keeping pace with one another: '"You should be finishing the first deal," or "second deal,", and so on.'. Once everyone has completed the first game, tables are changed as outlined below, and then the second game continues similarly. Sheinwold says "Four or five games make a very enjoyable session."., but obviously you can play as many or as few as suits your group.

If you wish to play in fixed partnerships these can either be agreed beforehand, or decided at the start of the session by cutting cards (or even a mix of both). Partnerships should generally be pairs, but some may be of three people if needs be (or if desired - play how you like!). Each partnership stays with the same pair of trump suits for the session. The Spades/Hearts players stay at the same table for the session, but after each hand the Clubs/Diamonds players move to the next highest-numbered table (wrapping around from the highest-numbered table to table 1). Any tables of five or six will need to play according to the rules for five or six, and the teams of three should ensure that between games they alternate the order in which they sit out, to ensure that a different player misses out on two hands each game. Each partnership has a 'tally card', and after each game they make note of the difference in scores as a plus/minus figure. At the end of the session, each partnership sums up all of these figures, and they can all be ranked. A check can be made that these totals added up across all partnerships comes to nil, to help catch potential errors.

If instead you want to play for individual scores, fill up the tables initially by whatever method suits best. Then before each game, at each table, players cut for partnerships. Play at each table is still in partnerships (following the standard rules for tables of four, or the version for five or six if you have any larger tables) - it's just that partnerships will change after each game. After each hand, the winners stay where they are, and the losers move up a table. Before the start of the next game, there is another cut, with the highest newcomer (who just lost at a different table) playing with the highest remaining player (who just won at this table). This means that the partnerships get shuffled up as the games go on. Each player has their own individual tally, making note of their partnership's winning/losing margin after each game. At the end each player will have an individual total. Some tables may have five (or perhaps even six) players - in such cases still the winners stay where they are, while if there are three on the losing side, two move up a table, and one moves down, to aid the shuffling process. Tables should be set up initially with the larger-player-number tables spread out as much as possible so that the same players don't end up in the larger tables always.

All games are played as dealt at the table. If you wish to try and balance the variance of these distributional differences, you could try a larger-scale version of Duplicate Calypso.

Calypso for Two

Kerry Handscomb (of Abstract Games magazine) has devised an interesting version of Calypso for two players, using a shortened deck, and a mechanism for player's personal trump suits to vary from trick to trick.

Read the full rules for Calypso for Two, or if you try it out, give feedback here.

Calypso Duet

Calypso Duet is a version of Calypso for two players — Calypso for two. It is essentially double-dummy Calypso, with a tiny twist. I wouldn't be surprised if others had played around with something of this nature (though I am not aware of any specific attempts), but this is my version.

As Bridge players will be familiar with, a dummy hand is a hand of cards which is visible to all. The cards do not really belong to an independent player - instead the player opposite plays both their own (secret) hand, and the dummy (being their partner). In each hand of Bridge a single hand is dummy, so that each player knows the contents of precisely two hands - their own, and that of dummy.

Double-dummy is the situation where there are two dummy hands. This means that players know the contents of three hands - the two dummies, and their own. In a game like Bridge, where all cards are dealt out, this allows players in fact to deduce all hands (the fourth hand necessarily contains all the missing cards). As such, the game turns from one of hidden information, to a game of perfect information. There is no need to deal with risk/uncertainty, as all cards are known. This takes a lot of interesting features out of the game. While double-dummy Bridge may occasionally be played (and is not completely trivial in all cases for humans), it is most often employed using computerised double-dummy solvers to aid to players get a rough sense of what sort of results might be achievable.

The situation in Calypso is different, however. As only a quarter of the cards are dealt out at a time, a player cannot fully determine the contents of the fourth (the opponent's secret hand). With perfect memory, in the fourth hand, a player certainly could, but most of us will at best be able to deduce a few cards, and perhaps the suit distribution, so there is perhaps some interest to be had in the game. Even those with perfect memories will only have to play without uncertainty a quarter of the time.

The actual rules of Calypso Duet are almost identical to Standard Calypso - the only differences lie in the setup of each hand. Players select suits by some means - one player will have the major suits (Spades and Hearts), the other the minor suits (Clubs and Diamonds). For each player, the red suits (Hearts and Diamonds) will be the trump suits of their dummy hands, whilst the black suits (Spades and Clubs) will be the trump suits for their secret hands.

Four hands are then dealt out, as usual - each player receives two distinct hands, face down. Each player then picks up one of their hands and inspects it (if you don't want to have to rue a meaningless choice, you may agree to pick up the one on the left). After inspecting the hand (but not looking at the hand remaining on the table), they must each decide if this hand will be their secret hand, or their dummy. They do so by placing the hand face down in a pile either:

- directly in front of them, to indicate it will be their secret hand

- clearly to one side, to indicate it will be dummy

Alternatively, if you are very keen that this decision be made simultaneously, you can agree some way to each note your decision, revealing after you have both decided, such as:

- writing the choice on a piece of paper

- secretly placing a coin one way up (heads for dummy, tails for secret)

- using one of two distinct jokers (if your packs contain them)

It shouldn't really matter, as it is unlikely your opponents decision should affect yours, but you are free to make such an agreement if you prefer the symmetry.

Once this is decided, players pick up their designated secret hand, and trickplay begins. Each hand starts with non-dealer leading a card to the first trick. Dealer then exposes their dummy, and plays a card to the trick. This is followed by non-dealer exposing their dummy, and playing from it to the trick, before finally dealer finishes the trick with a card from their hand. Play then continues through the rest of the hand following usual Calypso rules. Both dummies remain exposed throughout.

After the first hand is finished, deal switches, and the same procedure is repeated for the next hand:

- Players look at one hand and choose it to be either hand or dummy

- Non-dealer leads from hand

- Dealer exposes their dummy and plays from it

- Non-dealer exposes their dummy and plays from it

- Dealer plays from hand

- The rest of the hand plays out with standard Calypso rules

There are some points to note. One is that, compared to an ordinary game of Calypso, the deal does not 'rotate' properly, nor does the order of hands remain fixed. Instead, the order of play effectively reverses each hand. For instance, if the major suits player is dealer, the order of play to the first trick of each hand is:

- Clubs, Hearts (dummy), Diamonds (dummy), Spades [major suits player is dealer]

- Spades, Diamonds (dummy), Hearts (dummy), Clubs [minor suits player is dealer]

- Clubs, Hearts (dummy), Diamonds (dummy), Spades [major suits player is dealer]

- Spades, Diamonds (dummy), Hearts (dummy), Clubs [minor suits player is dealer]

Another point to be aware of is that, if you are leading to the first trick, you have no knowledge of the cards in your dummy at the point of leading ,if you choose your initial hand as your secret hand. You only discover the contents of your dummy at the same time as your opponent, after they have played a card from their dummy to the trick. Obviously if you choose your initial hand as dummy, then when you come to lead from hand you will have seen the cards in dummy. However, you may not refer to them again until the dummy is publicly exposed.

The reason for fixing the trump suits of dummy hands, and keeping the order of play consistent (relative to dealer), is made to help players easily remember the state of the game, rather than risk getting confused about which hand has which trump suit, and trying to remember which hand is to play next.

This can be aided by the table layout. Assuming players sit opposite each other, it minimises confusion if both players keep their calypsoes of both of their suits (in-progress as well as completed) in front of themselves, rather than in a square. Additionally, players should place their dummies (once revealed) in the relative position of play. So when Clubs leads first, the dummies should be on the Clubs-player's left (and the Spades-player's right), with the Hearts dummy to the left of Clubs, and the Diamonds dummy to the left of Spades. The next hand the two dummies will be on the other sides (to the right of the Clubs player, and left of Spades).

If play is slow/interrupted, it may prove useful to have a marker of some kind (a poker chip, or coin, for example), to mark the hand who is to lead next.

Call-and-response

There is also a version of Calypso Duet called Call-and-Response. The additional feature in this version is the addition of a card exchange element, which adds an opportunity for just a little extra strategy. Play of the game is as in 'vanilla' Calypso Duet, except for a modification at the start of each hand.

When players are investigating their initial hand (and deciding whether it is secret, or dummy), they additionally select three cards from the hand, and place them face down to the side. These three cards will become part of their other (currently unseen) hand. How this then plays out depends slightly on whether you choose this (the remaining ten cards) to be your secret hand, or your dummy.

If you choose it to be your dummy, then you place the remaining (ten) cards in the usual position for dummy. You then pick up the other hand as usual (your secret hand) and, before the first trick begins, you select three cards from your hand, and add them to the dummy, shuffling them together (so as not to reveal to opponent which cards were passed once dummy is revealed). You then pick up the three cards that you set aside originally, and add them to your hand. Then the first trick can begin.

If instead you choose your intial hand as your secret hand, then the procedure is slightly different. Firstly, if you are non-dealer, you must lead from the hand of ten cards initially. For both players, as it becomes time to reveal their dummy (i.e. when dummy is about to play to the trick), you should first place down your secret hand, and pick up dummy. Select three cards from dummy, and place them into your secret hand (thus creating a full hand once more). Then pick up the three cards initially set aside, mix them into dummy, and then carry on as before (i.e. expose dummy and play a card from it to the trick).

Obviously players need not make the same choices as one another, so each follows the relevant procedure. The rest of the hand plays out as usual - this process is then repeated before the start of the other three hands.

Coöperative Calypso

An interesting change of pace you may wish to try is to play a coöperative version of the game. Rather than two teams competing against one another, the aim for all four players is to maximise the total score.

The rules of the game are identical to that of Standard Calypso, and the scoring is also identical. The only difference is that instead of each partnership adding up their scores, all four players total their score as a total for the table. Players are aiming to try and maximise this score.

It is important to note that in particular the rules on where cards go upon trick-completion are unchanged. This is what keeps the game being completely trivial — everyone is trying to arrange situations so that as few cards as possible go into the trickpiles, and that each partnership wins only cards containing their own suits before transferring the lead to the other partnership.

As usual, players are not allowed to directly communicate about their hands (I'm not certain that this would make the game completely trivial, but at the very least would probably grind it down into over-analytical). However, players are free to communicate indirectly by creating card-signalling systems. In a coöperative setting there is perhaps greater scope for signalling conventions, and it may be possible to extend signalling from the standard game to cover a wider range of settings.

Of course the downside of this version of the game is that the ending can feel a bit flat. You may be able to discuss moments in the game where in retrospect you realise you could have earned more points, but ultimately it is hard to know how well you have done as a team. There is no easy fix for this, as there is no straightforward way to tell what the maximum possible score you could have had was, with the cards dealt as they were (short of inputting the entire set of deals into some kind of quad-quadruple dummy solver).

However, as a very crude tool, I suggest the following score bands (with corresponding possible total table calypsoes) translated into 'grades' (borrowing the idea from other coöp games):

- 2080-2449 Impressively terrible. Presumably concerted sabotage from all parties. (no calypsoes)

- 2450-2999 Very bad. I think you know that. (0-2 calypsoes)

- 3000-3499 Bad. Not quite as many points as you would expect playing against one another. (2-3 calypsoes)

- 3500-3999 Okay. Just about working together. (2-4 calypsoes)

- 4000-4499 Decent. Starting to look like a coördinated team. (3-5 calypsoes)

- 4500-4999 Good. A respectable score. (4-6 calypsoes)

- 5000-5499 Very good. Calypsoes as far as the eye can see! (4-7 calypsoes).

- 5500-5999 Amazing. Playing in beautiful harmony. (5-7 calypsoes)

- 6000-6999 Absolutely outstanding. A champion score. (6-9 calypsoes)

- 7000-7999 Borderline implausible. A well-orchestrated tour-de-force! (7-10 calypsoes)

- 8000+ I've run out of superlatives. You embody the true spirit of Calypso. (9+ calypsoes)

Competitive Coöperative Calypso (Duplicate Coöp)

If you find yourself in the flush position of possessing eight willing players (and as many packs of cards), then you can bring a competitive element back to Coöperative Calypso, by playing one table of four against the other.

In general the deal of the cards will play such a large role as to render it largely pointless to compare. However, if you have the patience to do so, you can arrange to have identical deals as in Duplicate Calypso, so that you can truly compare like-with-like, and any differences in the final score will be solely down to the respective card-play of each table.

With just four players, you can instead split into two tables of two. Ideally still arranging the two quad-decks identically duplicate-style, there are three options available:

- Play standard Calypso, with each player playing both hands of a partnership. Care must be taken to not confuse the two hands, and to keep track of leads, etc.

- Do similarly, but players instead have one hand of each partnership (one player has the black suits, the other the red suits). No difference in rules.

- Instead of Standard Calypso play Calypso Duet coöperatively. As the two tables may have different cards then exposed in the dummies, care should be taken to make sure the two tables cannot see one another during play. Whilst the extra information of the dummies may make this version a bit easier in the play, the addition of the card exchange allows for some level of variety.

If there are only two of you, you may wish to try playing quadruple-dummy coöperative against one another. Each player plays all four hands at one table, and scores are compared at the end. To stop this version being too dry and analysis-heavy, I suggest a time limit per hand. Four-and-a-half minutes per hand gives a little over five seconds on average per card, which might seem a bit generous, but also accounts for all the admin of sorting cards post-trick. If this is too luxurious, I think three minutes should be achievable. Probably a penalty of -10 points per second over time should be sufficient to stop too much dawdling.

Embers Calypso

Embers Calypso, or alternatively Calypso Continuo is a simple variant of my own invention, where the Calypso keeps smouldering along as any number of hands are played.

The aim is to try to soften some of the extremeties of distribution in the standard game (where for instance losing all four of a rank of your trump suit in the first deal can mean you are destined for no Calypsoes with three hands yet to play), and additionally to allow the game to be played to an arbitrary number of hands (so that you may continue play without needing to commit to a further four deals). Additionally, the number of duplicate decks used is only three — but see note at the end for using other numbers.

Play is for a fixed number of hands, the number of which should ideally be agreed beforehand. Four is the bare minimum, but twelve is probably a decent number - of course choose whatever suits your taste and timescale. If not agreed beforehand, players can choose whatever system they like to draw the game to a close --- ideally the number of hands played should be even, so that both partnerships have had the initial lead an equal number of times.

Cards are shuffled and dealt as in the standard game, and the first hand is played as usual - this hand is known as the fire>. Thereafter, from the second hand onwards (these are the ember hands) however, there is a procedure to follow at the end of each hand — the play during the hands themselves is no different than the standard rules. To describe, we will refer to two (face-down) piles of cards:

- The green room, which initially is the remainder of the undealt cards (i.e. the 52 cards [or more if you are using more than three decks] that were not dealt out in the first two hands),

- The sin bin, which is initially empty

It should be relatively easy to distinguish the two, as there will always be significantly more cards in the green room than the sin bin, but for avoidance of confusion it is best to stack some of the cards of the sin bin perpendicularly to the remaining cards to help further distinguish the two piles.

After each hand is finished, the following procedure should be followed:

- Any completed Calypsoes are scored (with usual values: 500 for first, 750 for second, 1000 thereafter), and the cards from completed Calypsoes are added to the green room

- Any cards in the sin bin are also added to the green room

- Any cards in trick-piles are scored as usual (10 each), and put aside to form the sin bin for the next hand

- The green room is thoroughly shuffled, and a new hand of thirteen cards each is dealt from this deck, with the remainder being set aside as the green room for the next hand

The green room is thus the set of cards from which the next hand will be dealt, while the sin bin is the set of cards that 'sit out' for a hand. Cards that end up in trickpiles won't be available for the next deal (nor of course cards that form part of in-progress Calypsoes) - but the remainder of the deck (including those won from just-completed Calypsoes) will be.

Play of the hands themselves proceeds identically to the standard game. At the end of the final deal, any in-progress Calypso cards are scored as usual at 20 apiece, along with the final set of trickpile cards. Highest-scoring partnership wins.

This form of the game changes the dynamics somewhat - depending on the length of play, scoring Calypsoes becomes even more important, as the opportunity to reach the high-scoring 1000 point third-or-subsequent Calypsoes (one might call them millenary Calypsoes) is greatly increased. Completing Calypsoes also means that cards of your trump suit will be immediately available for the next hand. Trickpile cards also become increasingly valuable as compared to in-progress Calypsoes (as the former are scored continuously, whilst the latter only scores at the end of the game), as well as potentially 'locking away' valuable opponent cards for a hand.

Playing with other number of decks

Embers Calypso can be played with more than three decks, if you so desire. Three is the minimum number, as you have

- Up to 48 cards (nearly one deck) on the table in partial Calypsoes

- Up to 52 cards in the sin bin, once we are in the ember hands (if everything in a hand goes to trick-piles)

- We need at least 52 in the green-room to deal the next hand

With four or more there are enough cards to play more 'fire' hands if desired - up to the number of packs minus two. So for example with six decks, you could play four fire hands (i.e. you only start the sin-bin/green-room process at the end of the fifth hand). The more packs you use, the less you know about the cards available in the current deal. With three, you could almost know the entire set in some circumstances (if you have a good memory) - if you have 48 in-progress Calypso cards, and the previous hand went all to trick-piles, the next hand will be dealt from the remaining 56 cards. In practice there will be more than this, but you should have a better idea about the distribution more often than in the standard game.

Kaiso

A game inspired by Willis' original game, in which players can collect a variety of different card sets, rather than just calypsoes, of my own invention. See Kaiso page for details.

Auction Calypso

A variant of my own in which players bid for the right to choose the trump suits in exchange for committing to winning a certain number of points. See Auction Calypso page for details.

Quasi-related games

The following games are not really Calypso variants at all, and certainly don't qualify under my proposed criteria. Nevertheless, they each share some characteristic or other with the game, and so I mention them here for those who may be interested.

As far as I am aware, unless otherwise mentioned, they were all developed independently of Calypso, and were not inspired by it in any way.

- The game Trumps by Stan J. Towianski features trump suits which are personal to each team. The trickplay rules are slightly different than in Calypso, in that highest trump wins, regardless of whether this was by following suit or not. This is a possibility I describe when discussing personal trump suits.

- Jørgen Ravn Hagen's Evil Deal features a different notion of personal trump suits — each player has an associated suit, and this is a universal trump suit (i.e. a trump suit in the classic sense, being the same for all players) for any trick to which they lead. This might perhaps better be viewed as a trump suit that varies from trick to trick, depending on the lead.

- Cardigan, by Jared McComb, does not have personal trumps, but is a partnership game played with a 208-card quadruple deck, played out over four deals. There are substantive bonus points available for capturing (in tricks) full sequences of individual suits, as in Calypso.

Where to play?